Iamvery

The musings of a nerd

Getting Started with Elixir Metaprogramming

— May 19, 2016

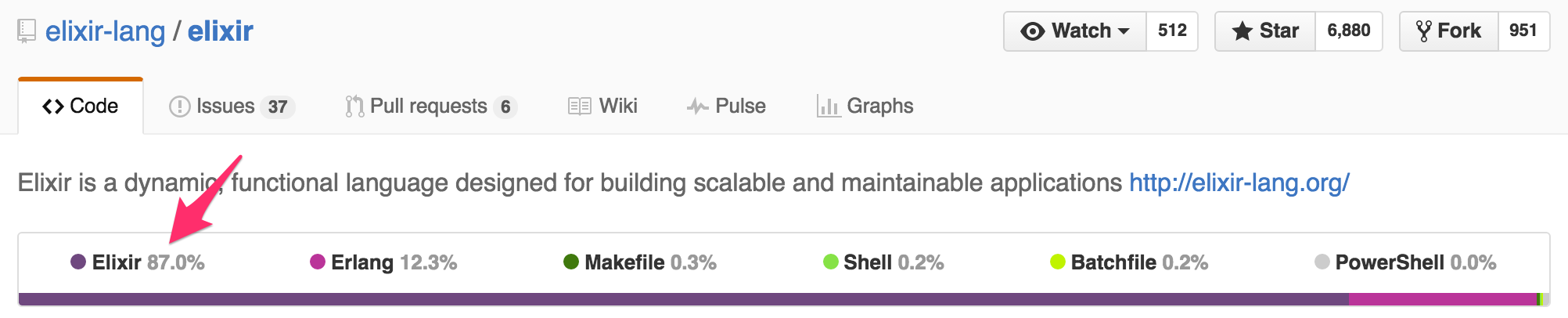

After spending a little time with Elixir, you might have found out its secret. Elixir embraces metaprogramming. In fact most of Elixir is written in Elixir.

Let that sink in.

Even if you exclude stdlib and tests, the majority of Elixir—some 75% of it—is Elixir. What is this magic?

Elixir is Macros

Mostly, it’s macros—major core features of Elixir are implemented with macros.

But what is a macro?

macro: a single instruction that expands automatically into a set of instructions to perform a particular task — Dictionary.app

That’s exactly it.

Elixir uses macros to provide interfaces for expanding complex sets of instructions during compilation. For example, the if construct in Elixir is a macro. It expands to a case statement, and it exists to make your Elixir code easier to read. So an if statement expands to a case statement similar to the following:

if worked? do

IO.puts("It worked!")

end

case worked? do

true -> IO.puts("It worked!")

_ -> nil

end

The compiled result of using the if macro is exactly the same as writing the case itself. In practice, macro implementations end up being way more complex than that, but it’s all just expanding statements. No magic.

Quoted Expressions

When programs are executed, expressions are often converted into abstract syntax trees (AST) for evaluation.

Elixir is no exception. In fact, you can access these structures yourself by using Elixir’s quote function.

You might think of quote as being similar to eval in other languages like Ruby. However, eval takes a string of code that is evaluated at runtime. This might lead to confusing, bug-ridden code or significant security concerns (remote code execution). Quoted expressions, on the other hand, are compiled so you still have the convenience of building code dynamically without the concern of runtime issues.

Say you want to build an expression that calls a function foo/1 with the argument :bar:

expr = quote do

foo(:bar)

end

IO.inspect(expr)

# {:foo, [], [:bar]}

The resulting 3-element tuple is an AST. Turns out these tuples are the building blocks of Elixir. Each position in the tuple has a purpose. They are often thought of as {form, meta, args}. form is an atom representing the name of the function being called in the expression. meta is used for context, e.g. imported modules (see below). args are the arguments to the function. Complex Elixir statements are accomplished by combining these quoted expressions:

expr = quote do

1 + 3 + 5

end

IO.inspect(expr)

# {:+, [context: Elixir, import: Kernel], [{:+, [context: Elixir, import: Kernel], [1, 3]}, 5]}

This expression includes metadata ([context: Elixir, import: Kernel]). In this case it’s used to inform its reader where to find the + function. If you were to manually evaluate this expressions, it would go something like this:

- The outer expression states: call

+with arguments[{:+, ...}, 5]. - The first argument hasn’t been evaluated, so it must be evaluated itself by calling

+with arguments[1, 3], which results in4. - Finally outer expression can be evaluated, calling

+with args[4, 5]which results in9.

Traversing Expressions

Complex quoted expressions are structured as deeply nested trees of nodes. Elixir provides a mechanism for traversing these ASTs with Macro.traverse/4:

pre_traversal = fn node, acc ->

IO.puts("before: #{IO.inspect(node)}")

{node, acc}

end

post_traversal = fn node, acc ->

IO.puts("after: #{IO.inspect(node)}")

{node, acc}

end

expr = quote do

"foo"

end

IO.inspect(expr)

# "foo"

Macro.traverse(expr, nil, pre_traversal, post_traversal)

# before: "foo"

# after: "foo"

As you can see, before and after each node is traversed, the respective function is called. These “pre” and “post” functions accept two arguments, the “node” in the expression and the “accumulator”, we’ll touch on this later. Additionally they must return a tuple of the node and accumulator. These functions can be used to gather information or make changes to the expression as it is traversed.

You might be wondering about the second argument to Macro.traverse/4. This argument is an “accumulator” that is passed into the function called at each node. Use the accumulator to count the number of sub-expressions in a quoted expression. For your convenience, Elixir provides shortcut functions Macro.prewalk/3 and Macro.postwalk/3 to call before or after traversal respectively:

counter = fn node, acc -> {node, acc+1}

expr = quote do

foo(:bar)

end

IO.inspect(expr)

# {:foo, [], [:bar]}

{_expr, count} = Macro.prewalk(expr, 0, counter)

count

# => 2, the literal :bar and the function call foo/1

Despite being called “accumulator”, this value may not only be used to gather information. Sometimes it is used to inject information…

Warning: You are approaching metaprogramming. Do not be afraid.

Metaprogramming

As you might have concluded from what you’ve seen so far, metaprogramming is fundamental to the implementation of Elixir. Metaprogramming in Elixir is all about manipulating quoted expressions.

One of the most basic examples of Elixir metaprogramming is transforming a quoted expression. In this contrived example, a typo is fixed in the expression:

expr = quote do

langth([1,2,3])

end

IO.inspect(expr)

# => {:langth, [], [[1, 2, 3]]}

Code.eval_quoted(expr)

# (CompileError) undefined function langth/1

expr = put_elem(expr, 0, :length)

# => {:length, [], [[1, 2, 3]]}

Code.eval_quoted(expr)

# => {3, []}

Armed with your knowledge of Macro.prewalk/3, you could traverse the expression and fix all the typos. Since you don’t need the accumulator, take advantage of the simpler Macro.prewalk/2:

expr = quote do

langth([1,2]) + langth([3,4])

end

fix_langth = fn

{:langth, meta, args} -> {:length, meta, args}

node -> node

end

fixed_expr = Macro.prewalk(expr, fix_langth)

Code.eval_quoted(fixed_expr)

# => {4, []}

Look at you! Writing Elixir with Elixir. :blush:

A Practical Example

I’ve spent some time recently working on koans for Elixir. Projects like this are used for learning programming languages. In general, they are examples that contain missing pieces to be filled in by the learner. The body of a koan might look like this:

assert ___ + ___ == 3

In order to progress to the next lesson, the user must replace the blank (___) with the value that makes the test pass. This works well for learners, but as a project author, it is desirable to know that, given the right answer, the koan pass without having to repeatedly solve the lessons yourself. Using what you know about Elixir metaprogramming, answers can be injected into these expressions before they are evaluated. Give it a shot!

koan = quote do

___ + ___ == 3

end

replace_blank = fn

{:___, _meta, _args}, [answer|rest] -> {answer, rest}

node, acc -> {node, acc}

end

answers = [1, 2]

{answered_koan, []} = Macro.prewalk(koan, answers, replace_blank)

{result, _bindings} = Code.eval_quoted(answered_koan)

result

# => true, because 1 + 2 == 3

This implementation traverses the expression with a list of values to substitute for blanks. Each time a blank is encountered, the expression is replaced with the head of accumulator list. The accumulator is being used as a queue. As long as the answers are in the correct order, the code is updated at compile time and the expected result is returned!

In fact, recently I had the hilarious realization that I accidentally implemented Macro.prewalk/3 to solve this very problem.

If you’re interested in seeing the above examples in code, check them out on GitHub.